- Home

- Annette Sharp

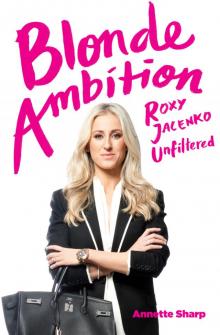

Blonde Ambition

Blonde Ambition Read online

In memory of Linda

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 715 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

[email protected]

www.mup.com.au

First published 2016

Text © Annette Sharp, 2016

Design and typography © Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2016

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Cover design by OetomoNew

Typeset in 12/16pt Bembo by Cannon Typesetting

Printed in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Sharp, Annette, author.

Blonde ambition: Roxy Jacenko unfiltered/Annette Sharp.

9780522870916 (paperback)

9780522870923 (ebook)

Celebrities—Australia—Anecdotes.

Businesswomen—Australia—Anecdotes.

338.092

Contents

Acknowledgements

1 On Trial

2 Scandal—A Means to an End

3 Rag Trade Heiress

4 Counter Girl Smile

5 Sweaty Betty

6 Love

7 Insta-mum

8 A New Brand—‘Roxy’

9 The Power Paradox

10 Under the Velvet Rope

Roxy’s character reference for Oliver Curtis

Acknowledgements

MY THANKS to those who played a role in producing this book: Louise Adler and Sally Heath for their faith; researcher Cathy Beale for her groundwork; Nick Jacenko for his patience in helping straighten out some of the creases in the fabric of Roxy’s history; Lisa Ho; a force of anonymous family members, friends and colleagues of key characters for helping me piece together Roxy’s story; my husband for his encouragement; my children for not being too cross when things slipped through the cracks at home while I was writing to a crazy deadline; two mentors called Peter; and my mother for continually pushing and catching me—and to Roxy who, although she declined my repeated requests for an interview for this book, helped shape it.

CHAPTER 1

On Trial

It was before my time. I don’t ask

Roxy

ON EACH AND every day of her husband Oliver Curtis’s 12-day insider trading trial, public relations supremo and reality TV runner-up Roxy Jacenko arrived at the front door of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, St James Road Court, punctually, with minutes to spare and just enough time to compose herself ahead of the Crown’s allotted 10 a.m. start.

As a large jostling scrum of press photographers and television crews would soon come to realise—just as key fashion, beauty, lifestyle and marketing writers across Sydney had discovered over the previous decade—Roxy was hardwired to produce a newsworthy ‘flashbulb moment’ for any media good enough to attend one of her promotional events. She had never disappointed when entertaining media on a client’s dime. It was hardly likely she would disappoint the biggest live media pool that destiny had yet divined for her.

For almost three weeks, the 70-metre stretch of St James Road from Elizabeth Street to the courthouse became Roxy’s runway, her arena.

If her husband’s criminal charges, in a case news outlets were already calling ‘the insider trading trial of the decade’, were going to propel her into the unforgiving eye of a media storm, she was going to be prepared. She might have even been over-prepared—which may, in the end, have served her less well than she would hope in a critical media’s eyes.

Not that she could have done anything else, for it was her way to give news agencies what she knew they wanted—something glamorous, captivating, sexy and a little shocking.

For the next three weeks it would be herself.

On 11 May 2016, day one of her husband’s trial, she wore a conservative knee-length Louis Vuitton dress, in black, with a logo belt and Yves Saint Laurent shoes.

On day two, she paired an all-business Saint Laurent dress, black again, with a Balmain power blazer—she loved Balmain and had a blazer in every colour—and her favourite spaghetti-string ankle-tie shoes by Saint Laurent.

She would maintain a generally conservative style until, in week three, feeling more relaxed with the intense media spotlight, Roxy would give her love of floral art its head in a pretty Mary Katrantzou printed dress with Azzedine Alaïa stilettos. The style was a departure for the practised power dresser but if there was one thing Roxy loved more than fashion it was an element of surprise.

For her twice-daily parade before the media pack camped outside the historic 1895 courthouse, Roxy would choose from an extensive wardrobe that made Sydney’s establishment and new rich green with envy. The feted names of the houses of Louis Vuitton, Balmain, Hermès, Yves Saint Laurent, Chanel, Gucci, Miu Miu and Céline would be uttered with less reverence in future days and weeks in Sydney’s privileged eastern suburbs as Roxy took luxury brands from the Paris catwalks and made them, shockingly said some, look outlandish in the sombre courtroom environment.

Her PR rivals would claim Roxy was seizing—no, hijacking—her husband’s court case. They speculated, based on the traffic and increased media interest in Roxy’s Instagram, the ambitious PR renegade had spied an opportunity. If she had, they mused, it might be the chance to shore up her PR business, which had surely been stung by the unacknowledged recession that had bitten down on the PR industry at large—their businesses too.

Roxy’s wardrobe would virtually dominate media coverage of Curtis’s trial. When one newspaper reported she had turned up at court in a black leather ‘laced lambskin’ Louis Vuitton dress worth $5469, dozens more picked up the story online and amplified it, so the revelation that Roxy knew her YSL from her ASOS from her 5SOS became one of the biggest stories on the internet in Australia for a month.

Twelve weeks later, heavyweight current affairs program 60 Minutes would ludicrously report it too.

Interest in her whimsical 1970s-inspired Mary Katrantzou smock and Christian Dior dress, her Balmain separates that stretched close to $10 000 an article and her pencil-heeled $1800 Alaïa stilettos was staggering. There had been some interest in the expensive Rolex watch she’d been wearing to court, though considerably less in her Cartier jewellery and $180 000 diamond engagement ring, but then the court photography probably didn’t do them justice.

After one Sydney newspaper, The Daily Telegraph, ran a photo gallery of her early courtroom ensembles, Roxy promptly took her cue and started shooting the images herself. If the newspapers were interested in her wardrobe choices, so too might be her 80 000-odd Instagram followers.

Each day, generally before the trial, she would snap a selfie in her apartment block elevator and upload the image to her photo-sharing social media app.

What she may not have realised as she posted her daily Instagram selfie was that a new generation of court reporters was monitoring her selfie activities, certain that by about 9 a.m. each day, Roxy, who was fast becoming a page three newspaper girl and the token ‘glamour’ on the six o’clock evening news, was making her way to court where she would be a welcome distraction from the next six hours of essentially dull courtroom reportage. The court reporters would promptly brief their photographer or cue their camera operator—today’s episode

in the nation’s insider trading drama was about to begin.

Roxy’s court selfies were, as was her habit on non-court days when she was happy with her outfit, routinely tagged. Roxy knew well the powers of Instagram. By tagging her clothes, her young social media admirers, snidely referred to by some as the ‘cult of Roxy’, would know just how highly she valued her public image and how much money and time she spent cultivating it. A tag might also generate inquiries concerning the designs at retail level, which in turn may push sales. Who knew? If there were enough inquiries for the garments and accessories at outlet level it might just feed through to the labels. It would be a fabulous thing to be a poster girl for a luxury brand and possibly sign a client like Louis Vuitton to her PR agency, Sweaty Betty—an agency that was missing an elite fashion brand from its stable.

If Roxy had helped shift the garments she’d worn from the racks of Sydney boutiques visited mostly by Japanese tourists and wealthy new Chinese citizens, none in the trade would say. This ugly insider trading affair was not a thing a person of good breeding cared to talk about or attach to a prestige brand.

Roxy paired every ensemble with a killer Met-Ball-worthy pair of heels that perfectly offset her toned limbs—the result of constant dieting and perhaps some yoga—and a fresh pedicure of pearly white toenails. Her nails put paid to the possibility she either would or could suffer looking matronly in a pair of pantyhose—that sensible foundation garment that suggested modesty and had been worn by conservative middle-aged women to court for fifty years. The whitened nails also complimented a midwinter tan that suggested Roxy, a well-travelled jetsetter, was only newly returned from a week in Antibes, France—a destination suited to her exclusive tastes.

Roxy arrived some days at St James looking pensive, other days, it seemed, in high spirits. She was, court reporters would murmur quietly into their takeaway pad thai, the most bizarrely glamorous thing New South Wales’s Supreme Court had seen since petty-criminal-turned-meth-dealer Simon Gittany’s 2013 murder trial catapulted Gittany’s exotic girlfriend Rachelle Louise into the spotlight.

‘Balcony killer’ Gittany had been convicted of throwing his ballerina girlfriend to her death from a high-rise city apartment balcony—a crime so heinous it alone should have satisfied the media’s gruesome appetite. However, it was his bombshell dark-eyed, LBD-wearing partner, Rachelle Louise, who soon dominated media coverage. Her courtroom screams, flood-of-tears flights, forecourt placard protests and trembling smokos had made for exceptional drama.

Sydney’s media hadn’t seen courthouse ‘sexy’ executed well more than a handful of times and as a result they were ready for whatever Roxy would bring. The female reporters in the court’s media room were enlivened by small talk concerning the PR boss’s designer wardrobe.

With her rockstar Ray-Ban Aviator sunglasses perched casually on the end of her newly remodelled nose, suspiciously plump lips fixed apart and a mane of freshly lightened extension-fortified hair curtaining her shoulders, Roxy was primed and ready for the most harrowing episode in her young husband’s life. And she looked sensational.

The sunglasses ensured the media rarely glimpsed the Sydney publicist’s eyes during her daily arrivals and departures. What she was thinking was anyone’s guess.

Her appearances on the evening news each night gripped the credentialled fash pack: Was the 36-year-old channelling Kim Kardashian, Cate Blanchett, Rosie Huntington-Whiteley or one of the many fashion bloggers she followed? Whoever it was, they overwhelmingly agreed she had nailed the look of ‘brittle New Yorker’ to perfection.

The one accessory that was pure Roxy was the mobile phone—traditionally a BlackBerry but of late an iPhone—gripped in one hand. In her other hand was the tidy paw of her expensively dressed husband—in tasselled leather loafers and Hermès ties expected to have set him back $800—who now stood accused of conspiring to commit insider trading.

The Australian Securities and Investments Commission’s (ASIC) plodding 7-year investigation had begun the year before Sydney’s most divisive PR woman and most controversial ‘Insta-mum’ had started her relationship with Curtis in 2010.

Oliver Curtis and John Hartman were 21-year-old best friends of almost a decade when they hatched a plan to trade using insider information Hartman acquired as an equities dealer at boutique investment company Orion Asset Management, so Hartman would tell a court at his trial in 2010.

Both Curtis and Hartman—like Roxy—had been born to industrious self-made parents and raised in the lap of luxury. They were the children of first-generation newly rich entrepreneurs, ground breakers with adventurous spirits who worked around the clock building wealth in order to create comfortable privileged lives for their children.

Of the three families—the Curtises, Hartmans and Jacenkos—the Curtis family was widely regarded in business circles to be the richest, while the Jacenkos were the dark horse. Nick and Doreen Jacenko’s wealth went largely unnoticed outside the rag trade community until their expensive property acquisitions and divestments started being documented in newspaper real estate columns.

Roxy’s father-in-law Nick Curtis had moved from investment banking into gold and rare earth mining in the 1990s and 2000s as the computer industry was booming. When the stock market crashed in 2008—the year his son was engaging in and enjoying the spoils of his insider trading—his father was being appraised by business magazine BRW for his Rich List potential. With an estimated personal fortune of $40 million, he was regarded as a solid candidate for a future rich list.

Within the minerals sector, Nick Curtis was lauded as both a visionary pioneer and a shrewd international negotiator. Having studied art history at university and graduated with honours in 1978, Nick Curtis, an art lover, decided to venture into the art business and for a time worked with well-regarded arts dealer Tim Goodman. He would joke in a 2010 interview that after selling enough art to bankers and stockbrokers he decided he needed to move to ‘the other side’. ‘I want to buy [artworks], not sell them,’ he said.

About five years before his son was born, Nick Curtis applied for a job as a futures broker at what was then Hill Samuel Australia. Appointed to the job, he rose quickly through the ranks during the 1980s and early 1990s to become boss of the commodities division and executive director of what by 1985—the year of his only son Oliver’s birth—had become the Macquarie Bank, known as ‘the millionaire’s factory’.

Banking would inspire his interest in gold. In 1993, he went to China looking for mining assets after meeting and striking up a friendship with a Chinese exports authority executive attached to state-owned interests. A $30 million Chinese investment in the Cayman Islands company Sino Mining International would mark the beginning of Nick Curtis’s years as boss of the company owning China’s second largest goldmine.

In 2002, Nick would list the mining business on the Australian stock exchange as Sino Gold. A year later, he would boldly and controversially attempt to mine Tibetan gold in Jinkang, eastern Tibet. Though popular with investors, the move wasn’t popular with the Australia Tibet Council, which produced a report in opposition to the project including a letter from the Dalai Lama questioning the ethics of the ‘exploitation of Tibet’s non-renewable resources such as gold’. Protests followed in Sydney, London and New York. Nick became the public face of the Chinese-aligned Sino—a company accused of trying to acquire what the Australia Tibet Council saw as Tibet’s future wealth.

It was an emotive battle that Nick and Sino would lose in 2004 after the company cancelled the project. But it wouldn’t hamper Nick’s ambitions. The banker turned prospector had already identified a new opportunity borne of China’s domination of rare earth mining, the tiny metals used in computers, missile guidance systems, iPods and hybrid cars. His company Lynas Corporation acquired a mine in Western Australia from one of Australia’s biggest mining-industry speculators, Andrew ‘Twiggy’ Forrest, who, as a future billionaire philanthropist, would offer John Hartman a chance at professional reh

abilitation.

After selling Sino Gold to Canada’s Eldorado Gold Corporation for $1.8 billion in 2009, Nick’s interests would be focused on Lynas Corporation, a company he founded in the mid-eighties and which the China Nonferrous Metal Mining (Group) Co. attempted to take a controlling interest in that year until warned off by Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board.

Described as a ‘corporate titan’ and ‘mining magnate’, Nick had become a rich and powerful man. In the financial year to June 2011 he made $3 808 720 including share-based payments at Lynas. In 2012, this rose to $4034 163.

Lynas Corporation, valued at $4 billion, was going gangbusters until Malaysia’s engaged and enraged Facebook community—and a slowing global economy—combined in 2012–13 to erase half the value of the company—events that coincided with Nick’s son’s professional downfall.

Nick’s plans to build the world’s largest rare earth processing plant in Malaysia had been met by overwhelming opposition from residents living in the Kuantan district. Frightened of the health and economic implications of having a mineral plant in their backyard, Malaysians resisted Lynas’s industrial expansion and protested in the tens of thousands on social media—specifically on Facebook and Twitter—to block Lynas Corporation. The result was that Nick’s company was tied up in judicial challenges for long months, costing the company a fortune. It was an unmitigated PR disaster.

The Malaysian plant was operational by December 2012 and by February 2013 had produced its first batch of processed metals—but in January 2013 Nick’s son Oliver, then aged twenty-seven, would be charged with conspiracy to commit insider trading on forty-five separate occasions.

Within two months, Nick would resign as chief executive of the company and take a non-executive position which would see his package drop to $1 726 551 in the year after. He would also transfer and sell down some twelve million shares in the company that he had founded.

Blonde Ambition

Blonde Ambition