- Home

- Annette Sharp

Blonde Ambition Page 2

Blonde Ambition Read online

Page 2

Nick and his wife Angela would snappily sell their Woollahra home for $10.5 million before moving, newspapers would report, into a rented property in vibrant Surry Hills, once the domain of Sydney’s battler migrant population. The experience in Malaysia would teach the businessman about the potential power of social media to galvanise a community to oppose and block industry. He would acknowledge in a 2012 interview that he ‘probably didn’t recognise the power of the social media to create an issue’.

In his new daughter-in-law Roxy, he would find someone who did comprehend that power and who wielded social media expertly—like a heavy-duty cleaning agent.

By the time Oliver Peter Curtis’s charge was before the court in March 2013, his former best friend John Hartman had already served a 15-month sentence in an informant’s wing of Silverwater jail. The court had determined the prison block was the safest place for Hartman, twenty-five at his 2010 trial, after he turned key witness against his childhood friend to reduce the severity of his own sentence for misappropriating $1.9 million in funds through insider trading.

Like Curtis, Hartman too had a famous dad.

To the women of Sydney, Dr Keith Hartman was more famous than mining investment adviser Nicholas Curtis, AM. Keith Hartman, AM was known in the social columns as the ‘obstetrician to the stars’. This was as a consequence of him having delivered the latest generation of Murdoch and Packer babies.

A father of six, Dr Hartman also had an entrepreneurial streak which was on show in 2007 when, with the backing of controversial property developer Albert Bertini and Shane Moran, a member of the wealthy healthcare family, he opened a private hospital for new mothers in an old Lavender Bay convent overlooking the affluent northern lip of Sydney Harbour. Called The Mother’s Retreat, the venture promised 5-star luxury accommodation and neonatal care to new mothers and their babies for $1300 a night. The $8 million privately funded centre was, Dr Hartman told The Sydney Morning Herald in 2007, ‘The only centre of its kind in the world that we know of’. Within a year, however, the project had failed—a casualty of poor timing with the global financial crisis biting shortly after its launch.

John Hartman and his friend ‘Oli’ Curtis grew up neighbours—two doors apart on Bradleys Head Road on Sydney’s affluent lower north shore at Mosman—a picturesque suburb where the average home costs upwards of $3 million, mini-mansions run to $20 million and real estate agents spruik the area as ‘a safe family haven beyond compare’.

Many of the houses in the suburb boast sweeping Sydney Harbour views, glimpses of the landmark Harbour Bridge and are a short stroll to the shark-netted basin known as Balmoral Beach, where Australian television and sports stars have, for generations, introduced their toddlers to saltwater paddling.

The neighbours forged a friendship at the prestigious and historic St Ignatius’ College Riverview during their high school years, from 1998 to 2003. The school motto Quantum potes, tantum aude—‘Dare to do as much as you can’—would resonate throughout the two men’s trials.

St Ignatius’ is located on the banks of the Lane Cove River and counts among famous alumni a former prime minister in Tony Abbott, a deputy prime minister and National Party leader in Barnaby Joyce, an archbishop of Sydney, a former NSW premier, the billionaire healthcare founder Paul Ramsay, the first Australian-born astronaut, internationally famous art critic Robert Hughes and his brother, former attorney-general Tom Hughes who was the father of Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s wife, the former Sydney lord mayor, Lucy Hughes Turnbull.

The men’s 2003 high school yearbook records Curtis ‘excelled in all aspects of curricular and cocurricular activities’.

According to the yearbook record, two things brought Roxy Jacenko’s future husband to the attention of his classmates. One was the unconventional ‘mullet’ hairstyle that fellow St Ignatius’ students believed Curtis had introduced to the elite school, and second was his car, a BMW it was said—the ‘best’ car any student in the year would drive to school, classmates James Fitzgerald and Ed Tighe noted a little enviously.

Hartman stood out for more enterprising talents, the yearbook editors observed. He is remembered by classmates for his ‘enviable leadership skills’, being an excellent all-round sportsman, a strong debater and vice-captain of his house. He also, they wrote, was able to ‘somehow get his teachers into more trouble than he did’.

After graduating from school, Curtis started a business course at the University of New South Wales. His father would later state in a character reference to Supreme Court Justice Lucy McCallum that his son ‘was already actively engaged in understanding the financial markets and the business world’ while at university.

In his second year, Curtis suspended his tertiary studies to take up a job at boutique investment banking and asset development group Transocean Securities as an investment banker. He won the job thanks to his ‘personal relationships’, his father acknowledged, and his career, Nick would say with pride, developed ‘strongly and rapidly’.

Hartman, meanwhile, had matriculated from St Ignatius’ to one of Australia’s most prestigious universities, The University of Sydney. By March 2006, Hartman had secured a job as an equities dealer at Orion Asset Management—in time to witness the market hit a high ahead of the global downturn. Barely a year later, after some months’ discussion and planning, the best friends started insider trading.

It was May 2007 when the pair walked into an Optus shop on George Street and Curtis bought his friend a BlackBerry phone. Hartman would tell the court his best friend assured him the encrypted phone would leave no trail of their efforts: ‘The only way to get the information from the BlackBerry is to pull the satellite out of the sky’—which was proved partly to be true as little evidence was recovered from the phone during investigations.

Hartman, who had already dabbled in insider trading in 2006 before stopping due to his fear of detection, later claimed the idea for the scheme had been Curtis’s. Curtis had come to the enterprising economics student with a plan while Hartman was still living at home with his parents in Mosman.

Setting up an account with stockbroking firm CMC Markets in Curtis’s name, Hartman would pass sensitive information to his friend via his encrypted phone and Curtis would trade on it, Hartman told investigators. The pair used a method called ‘front-running’ that would see Curtis buy or sell a stock based on his friend’s analyses ahead of a big order Hartman would place on behalf of Orion.

At that time, Curtis was earning more money than Hartman—$400 000 a year in bonuses alone—and had access to a fat family trust. As a result he could afford to finance the trades he and Hartman made, which were high volume, in the tens of thousands of dollars.

Hartman, by comparison, was on a base salary of less than $64 000 at Orion in 2007—though this increased to $350 000 with bonuses. He had a gambling problem to boot, one that had been eroding his finances since university.

The day after buying the BlackBerry phone, Curtis transferred $8000 from his Westpac account to his contracts-for-difference account with CMC Markets, and it was game on. The trades, he would explain to the court, were generally conducted when the pair needed extra money to boost their lavish lifestyle. The young chums were soon rolling in dough.

Asked how much they made gambling on the share price movements of companies including Woolworths, JB Hi-Fi, Caltex, Lion Nathan and Harvey Norman, Hartman would tell the court: ‘To begin with, tens of thousands, then into hundreds of thousands. In one year, I could not give you an exact figure, but millions of dollars.’

Luxury cars, motorcycles, expensive ski trips to Canada and gambling trips to Las Vegas would follow. A $60 000 Mini Cooper S convertible with $12 000 of accessories was a gift from Curtis—as was a $19 380 black Ducati motorcycle in November 2007. In the same year, Curtis, who Hartman described as a ‘show-off’, also bought his father a Ducati and his girlfriend a $130 000 car. Emails tendered to the court revealed Curtis covered accommodation and helicopter costs du

ring an overseas trip for Hartman and other mates, including a budget with the Spearmint Rhino gentlemen’s club in Las Vegas.

In 2008, flush with success, the two men moved out of their parents’ homes and into a modern luxury beachfront apartment overlooking Bondi Beach at 14 Notts Avenue.

‘I can imagine coming home from work and sitting out on the balcony looking at the beach and having a perv on the Bondi to Bronte [people] whilst having a beer!!’ Curtis said in correspondence to Hartman concerning the property they would rent for $3000 a week.

Between 1 May 2007 and 30 June 2008, the pair made $1.43 million in a scam many would later compare to The Wolf of Wall Street’s Jordan Belfort, whose memoir was published in September 2007, four months after Hartman and Curtis’s trading splurge began. The Martin Scorsese–directed film starring Leonardo DiCaprio would be released almost six years later.

The chums split the profits fifty-fifty, with Curtis paying for everything to conceal their crime from Hartman’s bosses. Curtis would even pay Hartman’s share of their rent. When Curtis moved his girlfriend Hermione Underwood, soon-to-be best friend and manager of Sydney bikini model and B-list celebrity Lara Bingle, into the new Bondi Beach apartment, Hartman saw only an upside: ‘Will she do all my washing for me?’ he half-joked.

Though they were raking in money, they were spending it fast. Hartman could burn through $3000 a day. The Australian Financial Review reported the doctor’s son blew $400 at Bondi’s Icebergs restaurant one Tuesday, then lost $1000 at Randwick Royal Racecourse, spent another $1000 at Sydney’s Cargo nightclub in Darling Harbour before finishing up dropping $750 at the Royal Hotel Paddington. Ahead of a meticulously planned trip to Las Vegas, Curtis transferred US$100 000 to the Wynn casino to cover expenses. But for all the jetsetting and high living, by the end of June 2008, cracks had emerged in the friendship.

At his trial eight years later, Curtis’s legal team would tell the court the men’s friendship broke down after Hartman started ‘moving in on girlfriends of close friends’. Some speculated the eager young punter may have made a play for Bingle.

As the mudslinging continued, Curtis’s lawyer would expose Hartman as a recreational cocaine user, a problem gambler and a shyster who once contemplated bribing a jockey. Hartman countered with the claim Curtis also had gambling problems.

By August 2008, Hartman had dropped Curtis as his trading buddy and was trading alone when his broker, IG Markets, became suspicious due to Hartman’s ‘mad keenness’ for CFDs—contracts for difference. The CFD trading saw him betting on the short-term movement of share prices and given Hartman’s similar ‘keenness’ for punting, the big wins from small outlays brought an added thrill. After deflecting an initial request from IG Markets for his employer’s trading approvals in late 2008, Hartman was informed by IG in January 2009, via email, that his $1.6 million account had been frozen.

Dr Keith Hartman would tell the court his son promptly informed his parents of his predicament, and the family would together admit Hartman to the mental healthcare clinic Northside where he would be placed on suicide watch. Bipolarism, Dr Hartman added, ran through his wife’s side of the family.

Hartman resigned from Orion (where a manager had spotted the expensive new Rolex on the young trader’s wrist and become suspicious) and presented himself for ASIC’s investigation into his insider trading, an investigation begun in January 2009 with Hartman’s confession. At his 2010 trial, Hartman pleaded guilty to twenty-five insider trading charges, with thirty-two more taken into account at sentencing. He was convicted of making $1.9 million fraudulently. His 4-year-sentence was reduced on appeal and he served fifteen months at Silverwater jail.

Hartman, twenty-five at the time, was the youngest person jailed in Australia for insider trading. Almost six years later, it would be Curtis’s turn to face the Supreme Court after ASIC presented its case again him—one built on Hartman’s admissions when he answered ASIC’s probing question: Where had he gotten the money for trading?

Roxy and Curtis looked innocent and very much in love as they came and went from St James Road Court holding hands each day. At least they had in the early days of the trial. On the proposed first day of the trial, newspaper reporters were astounded to come upon the couple dining alfresco with their legal team at nearby café Fix St James following a court delay. A jail sentence appeared to be the furthest thing from the sanguine and cheerful defendant’s mind.

Roxy would watch attentively from the front row of the gallery of St James as ASIC presented its case against her husband—as physically close as she could sit to him. She had as support a small entourage comprising members of Curtis’s sizeable and expensive legal team and one large bodyguard she had retained for the occasion. The paid bodyguard took up most of a single pew, which at one point drew comment from a court official asking the man to please move over and make some room for other courtroom spectators.

The defendant’s father, having spent almost seven years trying to see off his son’s insider trading charge, sat apart from his daughter-in-law and behind her. The pair exchanged words only briefly, court reporters observed. Looking grief-stricken, Curtis’s mother Angela made fewer appearances at court and had even less to say to Roxy.

In legal circles it was rumoured that Nick Curtis was picking up the tab for his son’s $700 000-and-rising legal defence. The law firm representing his son, Clifford Chance, had represented Lynas before, memorably in a land ownership dispute in Malawi, in south-east Africa, where Lynas had had its eye on a rare earth deposit. If Curtis’s trial went to appeal—and it would in October 2016—the tab would run to more than a million dollars, or so said gossipy members of the legal fraternity.

Curtis would deny, through his senior counsel Murugan Thangaraj, everything his former best friend, Hartman, alleged. The young investment banker pleaded not guilty.

The lives of Curtis and Hartman had been very different in the intervening years from 17 January 2009, when Hartman quit their Bondi apartment and went home to his parents in Mosman, to 11 May 2016, the first day of Curtis’s trial.

Two weeks after Hartman was jailed in 2011, Curtis proposed to Roxy with a ring the newspapers reported was worth somewhere in the area of $200 000. Two weeks after Hartman was released from jail in March 2012, Curtis and Roxy were married in an extravagant ceremony reported to have cost $250 000. Though then a free man, Hartman had not been invited. The schoolmates’ friendship was over.

Though he had lost his job at Transocean after being charged with insider trading in January 2013, Curtis fell on his feet scoring a flashy new job as an executive director at his father’s specialist investment advisory company, Riverstone Advisory, where it was rumoured he was being paid $470 000 a year to travel to China and negotiate largely on behalf of state-owned Chinese mining enterprises looking to buy assets outside of China. Nick Curtis estimated that during his three years at Riverstone, his son worked on $1 billion worth of company acquisitions.

Despite glowing character references from his father, his wife, his former boss at Transocean, from where he was sacked, his mother-in-law Doreen and others, on 2 June a jury found Curtis guilty of trading on forty-five separate occasions between 1 May 2007 and 30 June 2008, using a company he controlled to make more than $1 million. Both his mother and his usually stoic wife would shed tears. His legal team didn’t present a defence on behalf of their client. Curtis never took the stand.

In what looked like a choreographed departure, Roxy would, for the first time in twelve days, leave the court that day before her husband—effectively drawing most of the media waiting outside with her in a westerly direction towards Elizabeth Street. Her husband would exit St James Road Court a short while later with what was left of the press pack following close behind and head in the opposite direction. Media coverage would report the couple ‘separated’ after the guilty verdict—the implication being that the couple’s 12-day united front had finally been shattered.

Three weeks later, on t

he day of Curtis’s sentencing on 24 June, the couple arrived in a large four-wheel-drive with as much muscle as the car could haul. The well-documented 70-metre walk had become more challenging thanks to an even greater media presence—possibly on the back of Roxy’s extraordinary court fashion posts to Instagram.

Roxy, who advocated keeping a level head when dealing with difficult media in day-to-day PR engagements, had the tumult covered. She hired global security firm Unity, bigshots in celebrity transportation and specialists in sneaky vehicle changeovers in underground carparks, to transport her and Curtis in a black Range Rover that had previously been used to ferry visiting singer Justin Bieber around the city.

The security car would have set her back $1000 a day, the investment in muscle more. The Range Rover wheeled up onto the footpath in Queen Square, startling and scattering court reporters as the occupants frantically exited the car surrounded by their security detail of burly men. Had media interest in the case not been so immense, unsuspecting CBD shoppers could have been forgiven for thinking One Direction was making a court appearance and not the PR boss from the 2013 series of The Celebrity Apprentice. The melodrama was not lost on the magistrate.

Justice McCallum sentenced Curtis to a maximum of two years in prison, to be released after one year on a good behaviour bond. She dismissed a request from Curtis’s lawyers to consider the intense media scrutiny of Curtis in sentencing saying: ‘There is no evidence that Mr Curtis himself has invited media attention; he is not to be equated with his wife in this context.’

If Roxy missed the comment, she may not have missed the judge acknowledging that while her young husband had received ‘more than his share of bad press’ in the years preceding his trial, it was ironic that after ‘centuries of relative civility’, technological advances had allowed an ‘explosion of dissemination of medieval attitudes’—on social media.

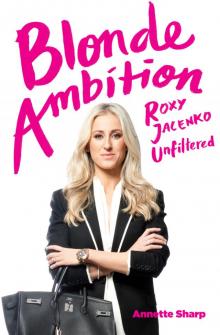

Blonde Ambition

Blonde Ambition