- Home

- Annette Sharp

Blonde Ambition Page 3

Blonde Ambition Read online

Page 3

‘It is troubling,’ the judge added, ‘that unlike Mr Hartman, Mr Curtis has not embraced responsibility for his offending’, and had expressed ‘no contrition to any degree whatsoever’ about his crime to ‘fund a lifestyle of conspicuous extravagance’.

‘While many people have spoken of his positive qualities in business and as a family man, he shows no sign of progression beyond the self-interested pursuit of material wealth which prompted his offending,’ she said.

Curtis took off his belt, tie, $13 700 gold Rolex watch and wedding ring, and removed a wad of cash from his wallet, which he handed to Roxy, who he kissed three times on the mouth before being taken to a cell downstairs. Roxy looked, despite her tears, resigned to her husband’s jailing.

Justice McCallum dismissed a request for leniency in sentencing saying Nick Curtis would ‘always look after’ his son, who was expected to be detained at Hartman’s jail, Silverwater, but would end up imprisoned in a police cell in Surry Hills before being moved to Parklea Correctional Centre further west and finally, a month later, to Cooma Correctional Centre, south of Canberra.

During the months leading up to the trial and after, Roxy maintained she knew nothing about her husband’s insider trading. In the six years they had been together, she had never asked Curtis about it: ‘It was before my time. I don’t ask,’ she told social writer Kate Waterhouse in 2012. ‘I think if there was anything more to do with it, it would have been pursued by the court, and it has and nothing came of it … It is good that it is finished.’ Though it wasn’t finished.

In August 2016, she restated the assertion to 60 Minutes reporter Allison Langdon: ‘It happened years and years and years ago, well before my time. Look, call me crazy. Some people would want to know [about their husband’s history], you know, the ins and outs of everything. I haven’t asked.’

She repeated the assertion in a character reference submitted to the court: ‘Prior to my attendance at the criminal trial I had limited knowledge of the case against Oli. These events occurred before I met Oli and it was not something that we discussed at the time I met him in 2010.’ (See the full reference on pp. 186–8.)

This struck many as odd. Roxy was a details person and by 2010, the year the couple met, ASIC’s investigation into ‘Oli’s’ insider trading was already a year down the road after he was hauled before ASIC in March 2009. Six months into their relationship, Curtis’s former best friend and flatmate stood trial and was convicted in a case that was broadly covered by the media. Had Curtis concealed these from her, Roxy still could have attended court with him in January 2013 after he was served with a court attendance notice—though it was inconvenient, clashing as it did with her shooting schedule for Channel Nine’s The Celebrity Apprentice.

And there had been other opportunities to familiarise herself with the charge being brought against her husband. His committal hearing in November 2013 had taken a full week—though it had regrettably coincided with one of Roxy’s book launches. His arraignment hearing in February 2014, at which he’d pleaded not guilty to the charge and been bailed, was another, though by then Roxy was eight months pregnant with the couple’s second child.

Her husband’s criminal conviction now had the capacity to tarnish Roxy’s carefully polished image and her business. She admitted in her court reference it already had: ‘I know I have lost some prospective clients and will continue to do so.’

If her Sweaty Betty public profile was to be believed, she had shed 60 per cent of her PR clients since marrying Curtis, though publicly she would say she had done so deliberately. There was every chance she was now fighting for her own career. Not that Instagram reflected that. During the 12-day trial, she had picked up thousands of new followers. She now was closing in on the milestone figure of 100 000.

CHAPTER 2

Scandal—A Means to an End

A lot of people … said ‘You know what? Fuck her’

Roxy

EVEN BEFORE THE trial, Roxy was well blooded in scandal and controversy. In fact she seemed something of a lightning rod for it. There were many already betting as she took her place in the gallery at St James Road Court for her husband’s trial that her knack for becoming the story would prove the ultimate test of her marriage to Curtis, a private guy from a famously private family.

Nick Curtis had never solicited media attention. He had given few interviews during his 35-year career and had not spoken publicly about the insider trading allegations levelled at his son. Having spent much of his career working with and for Chinese state-owned interests, Nick was accustomed to media inquiries being routinely shut down. The Chinese were renowned for their media censorship.

Roxy, in contrast, could best be described as notoriously accessible—but then she was in the publicity game. Fame and notoriety were her lifeblood.

As Roxy had learned when she opened the doors of her successful fashion PR agency Sweaty Betty PR more than a decade before the trial, the more noise the better when it came to public relations and promotion. She had been a plump-faced and largely clueless 24-year-old when she hung her Sweaty Betty shingle outside a building in the southern fringe Sydney suburb of Beaconsfield in 2004. In the intervening twelve years, she had come to dominate a corner of the industry, win the respect of sections of the media and create two more businesses—a talent agency called The Ministry of Talent and a hair bow manufacturing business named for her young daughter Pixie. In doing so she had reinvented herself as a self-made entrepreneur.

It hadn’t been easy and there were days when she’d wished she had made a fist of something else career-wise. As she would tell The Sydney Morning Herald’s Jane Cadzow in 2013: ‘I was gutsy, I was ballsy and I had chutzpah. There were a lot of people who said, “You know what? Fuck her”. But there were a lot of other people who said, “Good on her for having a go”.’

A consummate saleswoman who must have been a little annoyed she hadn’t been able to sell her husband’s innocence to judge, jury and the world at large, Roxy was hardwired to seize every promotional opportunity available. Intentional or not, the media coverage would indicate she somehow had managed to hijack her husband’s trial. While some believed this was a deliberate act to shelter Curtis from public scrutiny, others said it was an accident as Roxy didn’t know how to take a backseat. It wasn’t in her nature.

Roxy’s nature had been confounding people for years.

Depending on which side of the Roxy divide one stood, the PR maverick was either the unluckiest person in the world or the luckiest, the most controlling or most careless, the most selfish or most generous. Anyone who knew her would likely agree she was hard to define. It was often said that she was cunning, ambitious, calculating, dispassionate, shrewd and brash. She would likely agree. She was also relentlessly hard working, determined, fearless, innovative and fun.

Roxy was breathtakingly unapologetic about the characteristics some considered faults. In some circles she was labelled a bitch, psycho and the euphemistic backronym ‘see you next Tuesday’—the perennially shocking word young creatives and roadworkers loved and sometimes used affectionately.

Name-calling was to be expected in Sydney, a city where success was hard won and generally went hand in hand with suspicion, envy and a smear campaign. Former employees who had once worked for Roxy at her PR company Sweaty Betty—one of social media’s most conspicuous PR outfits—threw the ‘see you next Tuesday’ acronym around habitually. Roxy had become a demanding and tough boss in her quest to be the best and, after a dozen years in business, had worn some staff out entirely and lost the loyalty of many more.

‘I’m an obsessive compulsive and people can either like it or loathe it,’ she would tell The Sydney Morning Herald’s Cara Waters in 2016. ‘If a train is not driven by a train driver it is delayed. Not every staff member can hack it. That’s the truth.’

Roxy was, as she stated plainly on 60 Minutes in the aftermath of Curtis’s conviction, ‘very in your face’, ‘OCD’ and ‘a control freak’.

Like the refugee Bettys, Roxy’s PR rivals were comfortable using the word ‘bitch’ when referring to the Sweaty Betty boss. They wouldn’t lower their standards to use the crude acronym. They maintained Roxy had been undercutting them and stealing their clients for years. She had no respect for the established code that kept a dozen or so top agencies humming along sweetly without each cannibalising the others’ businesses too disruptively. They maintained Roxy was not only actively trying to poach their clients but that she was also offering to manage their clients for less—unbelievably sometimes for nothing—just to have a glut of established brands in her stable, another notch on her rebel belt.

Frequently muttered though often spat venomously, ‘bitch’ was also in popular usage among a group of pretty eastern suburbs women when discussing Roxy’s romantic conquests. Roxy had known more than a measure of success turning heads and stealing hearts. On occasion, she had laid claim to other women’s boyfriends, at least one fiancé and, it was rumoured, at least one husband. She had done so audaciously and without considering the consequences or heartbreak this might cause others, close friends of these defeated women would say incredulously. She had stolen one woman’s fiancé out from under her—in one night. This was an unforgivable violation of the sisterhood, many felt.

The unkindest term of all—‘psycho’—was expressed whole-heartedly by those who seemed perpetually confounded by Roxy’s interdependent relationship with the media. Roxy had managed, both because she was devilishly clever and could be wonderfully charming, to bring a number of journalists into her inner circle. Some journalists were dearer to her than members of her own family, or were for long stretches.

During times of personal and professional hardship and seismic family turbulence—including when her relationships were breaking down with her father and her sister, possibly irreconcilably, and her mother, not so irreconcilably—Roxy was inclined to overshare intimate details of her family battles with a handful of trusted journalists, an act which some believed was a betrayal of her own blood. In so doing she chanced winning these reporters to her cause in media commentary that invariably followed.

Even before she launched herself into Instagram in August 2012—where she had unprecedented control of her public image and could ensure her messages and client plugs were published without distortion—Roxy knew how to wield and manipulate the media as few of her Australian contemporaries did.

She had a finely tuned instinct for gossip and made a point of being on a first name basis with high-profile gossip and social writers. They provided her with space in their columns to promote her events and clients for free, sometimes subtly, oft times not, and she helped create the perfect self-sustaining circuit by feeding those same columnists what she could when she spied a celebrity out and about, often one of her own clients at one of her other clients’ establishments—a sort of cosy cross-pollination that worked for all. She never failed to pass on a tasty morsel and was known to be loyal to those she favoured.

In much the same way as the film character Dolly Levi from Hello Dolly believed ‘money … is like manure. It’s not worth a thing unless it’s spread around, encouraging young things to grow’, Roxy, the evidence suggested, believed gossip was like manure. It too was a thing to be used as fertiliser for her business. By distributing it carefully she would make herself utterly indispensable to some sections of the Sydney media. If it happened to help her and hurt a rival, that just made it sweeter.

After a few years in business, Roxy had worked herself into the epicentre of Sydney’s notoriously superficial and obsequious social scene. Should there be any unkind gossip floating about concerning Roxy or a client, she would learn of it early thanks to her media connections and was able to batten down the hatches with help from her network of new media friends.

And in tall-poppy-obsessed Sydney, there was always unkind gossip floating around.

It was either bad fortune or good planning, but it seemed that on average there had been at least one major scandal a year in Roxy’s life since she launched her PR business in 2004. In the years from 2010 to 2016, the rate increased exponentially.

In 2004, Australia was about six years into its obsession with British model Gabrielle Richens, briefly a mannequin for fashion brand Diesel where Roxy had cut her teeth as a publicist. Known as The Pleasure Machine thanks to an airline ad portraying her as a stripper, Richens’ claim to fame in Australia had been her 2-year love affair with Canterbury–Bankstown rugby league star Solomon Haumono, who she’d met either at a Sydney nightclub or on a street in 1996. Reports were smoky on how they met but Haumono had been knocked off his feet.

Richens—at one point described by Haumono’s best friend, fellow league star Anthony Mundine, as ‘stunning but dangerous’ and by Haumono’s own mother as ‘trouble, trouble’—was propelled into the headlines in 1998 when the $200 000-a-year football player went MIA in the middle of the rugby league season. Sports writers would say the love-struck prop had followed Richens home to England. In the six years that followed, Richens was everywhere—she was a lads’ magazine pin-up girl, a guest on the weekly television program The Footy Show, a lingerie model and a rent-a-crowd party guest.

The ‘stunning but dangerous’ Richens was also, by 2004—the year Roxy opened her PR agency—hanging with Roxy. Roxy’s admirers would roll their eyes and say she was always going to be drawn to Richens. She loved sizzle.

When the ‘It’ girl from Kent wasn’t crashing out of her stint on the Seven Network reality series Dancing with the Stars, the three-time British FHM 100 Sexiest Women in the World poster girl was on Roxy’s arm. The pair were spied keeping company at a Pink Ribbon charity ball and later turned heads salsa dancing at eastern suburbs hotspot bar Goodbar, where Roxy was quietly rumoured to hold a part-time job working the door. If there was one person who could get you noticed and ensure you made Sydney’s social pages, it was sex bomb Richens, who had moved on from Haumono with futures trader and property mogul Hamish Watson.

Watson, like the man Roxy would one day meet and marry, was subject to an investigation by ASIC prompting inglorious headlines. In 2003, Watson, then split from Richens, was banned for three years from dealing or acting as a financial adviser after he was found to be involved in a share-market scam called ‘washing’—buying and selling shares to create the illusion of a flurry of interest in stock.

A decade on, the disgraced futures trader’s and Roxy’s orbits would intersect again in an unexpected way. Watson—by then using the name Hamish McLaren—was identified as a self-described financial adviser who had scammed the well-regarded Australian fashion designer Lisa Ho, whose business had collapsed owing millions in 2013. Ho, a household name, would put her business into voluntary administration in May 2013—five days after meeting Roxy’s father, Nick Jacenko, with whom she would fall in love. By November 2004, Roxy was fast becoming a regular on the social circuit where she mixed with glamorous new friends including beautiful young Cronulla models Cheyenne and Tahyna Tozzi and older friends like then boyfriend, Sydney Grammar old boy Adam Abrams.

Abrams was then working as a humble PR agent for celebrity spruiker Max Markson, but history would prove him to be a man with ambitions similar to Roxy’s own. Within the decade he would move out of Markson’s office and launch his own PR agency, Un

o PR, where clients would include his friends Shannon and Dion Rivkin, sons of flamboyant entrepreneur, stockbroker and convicted insider trader Rene Rivkin, who tragically took his own life in 2005.

In 2009, Abrams would act as celebrity agent for the woman media dubbed the ‘Chk Chk Boom Girl’—Clare Werbeloff. Werbeloff claimed to be a witness to the shooting of 27-year-old boxer Justin Kallu outside a Kings Cross strip club in the early hours of one Sunday morning. When a Nine Network news crew arrived in the Cross to report the shooting, Werbeloff rushed to the camera with her version of events:

There were these two wogs fighting. The fatter wog said to the skinnier wog: ‘Oi bro, you slept with my cousin, eh.’ And the other one said: ‘Nah man, I didn’t for shit, eh.’ And the other one goes: ‘I will call on my fully sick boys.’ And then pulled out a gun and went: Ch-k ch-k boom!

The clip went viral, Werbeloff was signed to Nine’s A Current Affair and Abrams stepped in from the Kings Cross ether to act as her agent.

Werbeloff later admitted making the story up but managed to parlay a Ralph magazine topless spread from the stunt. A year later, Abrams would diversify into floating bars and nightclubs. Just months after the launch of Sweaty Betty, Roxy, showing an early flair for media control, discovered she could track missing underpants via newspaper social columns. When twenty-six pairs of Dolce & Gabbana jocks—retailing for upwards of $80—weren’t returned to her following a modelling job, Sunday newspaper columnist Ros Reines wrote a story—in effect sending a missive on Roxy’s behalf. The underpants, only slightly soiled, were promptly returned.

By January 2006, Roxy had managed to find herself a more famous handbag than Richens—one guaranteed to generate mentions and hits in both the gossip and the sports sections of the newspapers. Roxy had improbably hooked Manchester United soccer star Dwight Yorke. The Trinidad and Tobago World Cup captain—colloquially known as All Night Dwight for his rumoured sexual stamina—had been signed as the marquee player to Sydney Football Club in its inaugural season. Reports varied on whether he was making $900 000 or $1 million for the season in Australia.

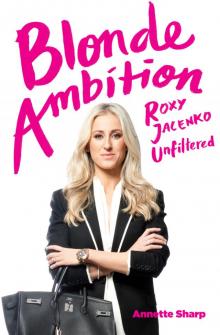

Blonde Ambition

Blonde Ambition